Early in director Todd Haynes’ The Velvet Underground, film critic Amy Taubin explains what was revolutionary about Andy Warhol’s 1963 film Kiss. Originally shown as a weekly serial, each segment documents a three-minute lip-lock between two people – couples of almost any and all stripes and combinations. Warhol’s early cinematic experiment is a reprieve from traditional filmic rhythms. Played at 16 frames per second instead of the standard 24, Kiss has a remove from reality in its silent unfolding. Taubin, a former Warhol Factory cohort, describes finding herself in tune with the subjects’ breathing and slowed heartbeats – a sensation that unfolded as a narrative wrought on a metaphysical plane, with her perception of time perpetually expanding and contracting.

Clips from Kiss are introduced here on top of the buzzy hum from early electronic drone musicians that made up the Dream Syndicate, a group to which Velvet member John Cale belonged. This collective was composed of like-minded artists who literally attuned their work to bodily frequencies as a spiritual practice, and their full-scale extended drone plays under Taubin’s narration. The frames that contain Warhol’s couples take up two-thirds of the screen with black space on the right. Ever the semiotician, Haynes is segregating the object for examination. The director isn’t simply showing Kiss or describing Kiss, he’s also contextualizing the work, its sensations, its intentions, and its relationship to contingent art scenes and movements of the time, including the music of the Velvets.

The name, the Velvet Underground, has always been evocative of a collective space and time, not a collective of individual pieces like Beatles or Rolling Stones. Appropriately for Haynes – who has already made narrative-cum-essay films about David Bowie and Bob Dylan that aren’t really about David Bowie or Bob Dylan – the Lou Reed-led band’s story is also the story of the art scenes of post-war NYC. The Velvet Underground was just one tendril that spun out from this incredibly fruitful era that saw experimental art movements creep into the mainstream.

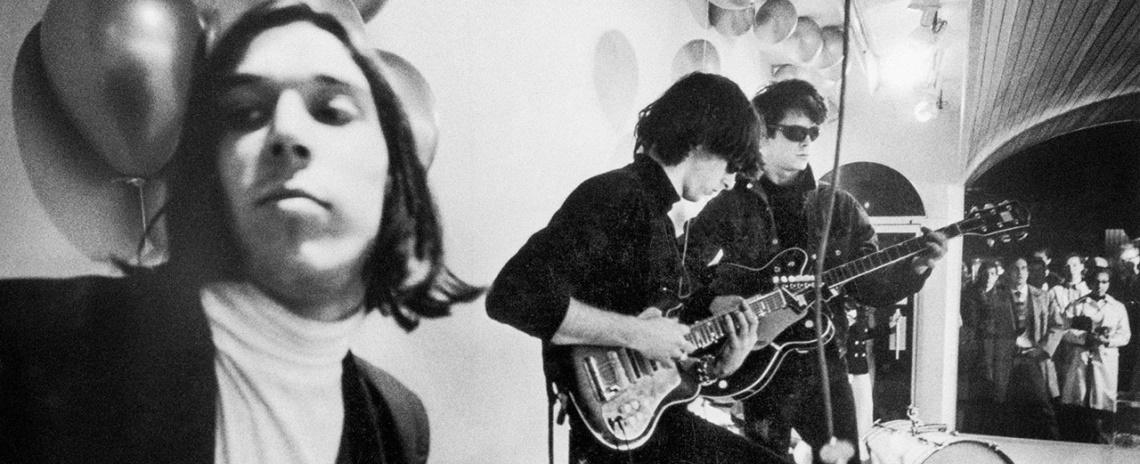

Among these creative agitators and misfits, the Velvet Underground are second only to Warhol, the “producer” who gave them the platforms of recording and avant-garde performance spaces, in name-recognition. The two have essentially overshadowed other figures like Allen Ginsberg, Jonas Mekas, Jack Smith, Mary Woronov, any other member of Warhol’s factory, Kenneth Anger, John Phillips, La Monte Young, Tony Conrad, et al. All of these figures are, in one way or another, present in Haynes’ kaleidoscopic vision of the era, as seen through the lens of the band’s brief, four-album lifespan from 1967-70. However, The Velvet Underground & Nico, White Light/White Heat, The Velvet Underground, and Loaded just so happen to be four of the great works of rock and roll.

Like Far from Heaven (2002) and Carol (2015), The Velvet Underground is very much the thing and a deconstruction of the thing: a complex trifle of rich yet complimentary layers that’s as confounding as it is intoxicating. The former was an exacting homage to the work of Douglas Sirk, a moving melodrama that also dissected the signposts and signals in Sirk’s work. The latter is the ultimate romance that gets to the heart of romance itself.

The Velvet Underground is the director and company – including editors Affonso Gonçalves and Adam Kurnitz and cinematographer Ed Lachman – tinkering with the conventions of the musical biodoc to create a more thrilling labyrinth of harmonic and dissonant ideas. Haynes’ latest is about the Velvet Underground, tracking Reed’s humble and delinquent beginnings as he found himself linked with Welsh musician Cale. His I’ve Got a Secret game show appearance gave his musique concrete and drone work an early spotlight before he joined forces with Reed, Maureen “Moe” Tucker, and Sterling Morrison to found the greatest rock band that ever was – at least according to the initiated few. Thankfully, The Velvet Underground refrains from making such statements and, what's more, it forgoes a typical biodoc convention: justifying its own existence through hagiography.

Those unfamiliar with the band will be able to glean their narrative and why they remain immeasurably influential, but the doc’s entry points are manifold, for both newbies and those familiar with its myriad subjects. With other archival footage – clips from contemporaneous underground films by Mekas, Smith, Anger, Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and others; rarely seen drug-fueled “happenings” featuring the Velvets; and a vast array of commercials, television programs, and other cultural ephemera – The Velvet Underground is a filmic version of pop art pioneer Robert Rauschenberg’s most well-known works. Haynes presents a graciously open-ended collage indexing an era and a milieu of the elegant and brutal, to steal a phrase from Cale, and this, his first proper non-fiction work, ranks among his best.

Rating: A-

The Velvet Underground is now playing in select local theaters and is available to stream from AppleTV+.