Ike and Tina Turner’s “River Deep – Mountain High” was a flop. When the single was released in 1966, it debuted at No. 88 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart. Pivoting away from the duo’s blues and rock roots and into producer Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” pop, the now-renowned recording was a point of contention in an already tumultuous relationship.

Ike, a possessive and destructive monster who’s seen by some as a grandfather of rock, reluctantly ceded some control over his wife and musical partner, Tina, by “letting” Spector use her insistent and resounding vocals as an instrument in the producer’s cavernous orchestration. Ike was invited to play guitar on the track but showed his lack of interest by not appearing for a recording session. His credit on any of the material birthed from these sessions – half of the 12-track album that takes the single’s title – comes solely from his legal, emotional, and physical possession of the singer.

Because of the single’s failure, that album would be shelved stateside for three years — until later cover versions of “River” renewed interest in the Turners’ original recording of it. Ike seemed to relish in Spector’s subsequent fall from grace as evidenced by a 1967 interview featured in Tina, the revelatory and vibrant new biodoc directed by Daniel Lindsay and T.J. Martin. He typically played the silent type to the public, but here he perks up when prompted to elucidate why “River Deep – Mountain High” didn’t connect with their fans. Turner pits Spector’s White sound against his Black one, stating Ike and Tina fans simply prefer the latter over the former. Although his hypothesis may be correct, Tina, seated beside her husband, appears angrily defeated nevertheless.

The filmmakers let the recording take its proper place as a pivotal moment in the narrative(s) of Tina Turner, the stage name given to Anna Mae Bullock after she started singing with Ike Turner’s band in St. Louis clubs during the late 1950s. Spector wasn’t plucking Tina out of obscurity; the personality and performer had already been well defined by the married duo act by 1966. As Tina suggests, the singer is owed as much authorship over the recording as is typically reserved for its producer. The invitation from him to go “River Deep” was an opportunity for Mrs. Turner to define her persona outside of Ike, whose music was known for one sound and one sound only. She had been sitting on the sidelines in creative conversations other than those about her trademark movement and style. As fans of the film’s subject now know, however, she was multifaceted beyond the imposed limitations that Ike had buttressed with psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. (Viewers should be warned that Tina does feature graphic descriptions of said abuse.)

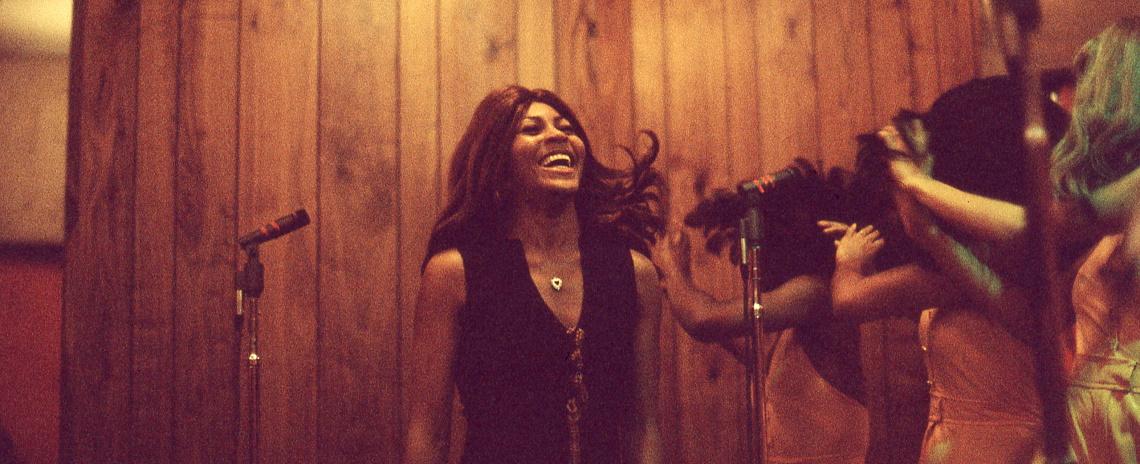

For the moment their film arrives at the recording of “River Deep – Mountain High”, Lindsay and Martin answer the call of Spector’s ever-intensifying crescendos with a demonstrative response of montage. A flurry of still photographs shows the singer pushing her body to what appears to be a breaking point, suspended in the exalted joy of creative freedom. She didn’t write it but it is her song: The title is the perfect description of the vocal range she exhibits, and the verses are escalating portraits of the queasy, unbending devotion she lived daily. The scene is a hair-raising collision of context, content, and form, with the only sound that can be described as both a pronouncement from the pearly gates and a march into the fiery depths of hell. But by this point, the effect isn’t necessarily surprising because Tina has already shown the directors’ uncanny ability to underlay their polished veneer with complex questions about celebrity, artistic identity, personal history, and social politics.

That the sound was shaped by the hands of Spector, another celebrated figure who was also a possessive and destructive monster, is an irony the filmmakers forgo highlighting here. This information doesn’t aid in the purpose of Tina as a gracious gift that returns ownership of its subject’s stories back to her, after she spent decades sharing them with the public.

What’s Love Got to Do with It, the meme-ified 1993 biopic focusing on the subjugation of Tina by Ike, has largely written the collective narrative of Anna Mae Bullock. Brian Gibson’s above-average adaptation of the performer’s autobiography, I, Tina, co-written with Kurt Loder of MTV News in 1986, gets its name from the title of her post-divorce comeback single from 1984. Angela Bassett, who joins Loder and many others as interviewees here, is shown in Tina seated next to the singer at a press conference during the 1993 Venice Film Festival. The actor carries herself in conflicted support of both the film that will bring her an eventual Oscar nomination and the woman whose tortured past she’s just portrayed on screen. It’s the same woman who, when questioned by the press corps as to why she hasn’t seen the film of her life story, rightfully yet respectfully proposes: Would you want to relive it if this were you?

What’s Love cannot be discounted as an urgent survivor's tale that has undoubtedly inspired others to action and out of similar situations. It’s also so ingrained in the cultural consciousness as the Truth about Tina Turner that some may even question the necessity of a new biodoc. The character in that film triumphed by escaping the violence and reclaiming her stage name in a 1978 divorce, eventually coming into her own personhood and artistry. It’s all true. These are events that happened to the real Tina Turner, and they’re even recounted here in the documentary about her, too. However, Tina also covers the next phases, showing that, more often than not, abuse and a survivor’s life do not end once contact ceases or the lights come up in the theater.

No one has let her truly escape him. Ike was even inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991, long after his ex-wife detailed her abuse at his hands, and a 2000 interview shown here details how he was allowed and maybe even invited to tiptoe around his destructive behavior right up until his death in 2007. Tina thought she’d end the Ike and Tina narrative for good by exposing all of it, but the world just couldn’t help but keep it alive.

At one point in Tina, an interviewer begins a line of questioning about their relationship. This is after the comeback, after the stadium tours, after Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (1985), after the book, after the movie, after Oprah’s Tina Day, and after the past had surely been exhumed for all it’s worth. The performer’s initial exasperation turns into physical discomfort and then into defiant ownership of her past. Finally, the trauma just manifests in a heartbreaking comingling of all of these reactions. They’re all the right reactions. They’re her reactions. She’s allowed to have each one of them, and to have them co-exist. She’s also a lot more than just them. People are complex, and they’re not easily summarized by a two-hour movie. (Thanks, Mank.) Tina understands this implicitly by simply working toward the complexity of a legend’s identity, but Martin and Lindsay also know just who gets to own it.

Rating: B+

Tina is now available to stream from HBO Max.