Sometimes it takes a beat or two for great films to reveal themselves. Director Samuel Fuller’s Japan-set 1955 crime thriller, House of Bamboo, opens with some gorgeous widescreen images of a smoke-belching locomotive chugging through a wintery landscape. The train abruptly crawls to a stop – there’s a broken farmer’s cart on the tracks – in a shot that permits Mount Fuji’s breathtaking snow-draped slopes to loom conspicuously in the background. The hobbled cart is simply a ruse, and in a matter of seconds, a brief delay turns into a vicious, meticulously planned cargo hijacking. This opening sequence provides Fuller (Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss) and director of photography Joseph MacDonald (Bigger Than Life, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?) to take the feature’s sprawling anamorphic CinemaScope format and eye-popping DeLuxe Color for a few warmup laps. Still, the scene is just as much a showcase for the deep pockets of 20th Century Fox, which bankrolled the film’s extravagant on-location production.

However, it's not until the six-minute mark that House of Bamboo truly begins to announce itself as capital-c Cinema. After the opening credits and some table-setting with Japanese law enforcement and the U.S. Army military police, Fuller and MacDonald punctuate a post-robbery scene at the train tracks with a gut punch of a low-angle shot: Mount Fuji again, perfectly framed between a dead man’s shoes. This is shortly followed by a stupendous long take that looks down on a claustrophobic trauma room, as doctors, nurses, and investigators crowd American serviceman-turned-gangster Webber (Biff Elliot), who has been shot by his own people. MacDonald pushes in on this scene so slowly it’s almost imperceptible, until a brief cutaway reveals that the MPs know about the hoodlum’s secret Japanese wife. The zoom then accelerates and slows again as it focuses on the dying Webber’s face, pulling the viewer into his sudden, desperate fear and the police’s fevered urgency.

Good stuff, but it’s only a taste of the visual splendor on display in this masterfully directed post-World War II film noir, which plays out against the uneasy, bustling backdrop of Japan’s rapid modernization. Admittedly, it takes some time for Fuller’s feature to settle into a story groove that feels as confident as its formal virtuosity. There’s a certain Dragnet-like starchiness to the plot for the first 30 minutes or so. It’s at once too convoluted and too anxious about losing the audience, resulting in a sense of hand-holding as it proceeds with dry, dutiful emphasis from one plot point to the next. As one might expect of a Hollywood picture set in postwar Japan, there are currents of deeply discomfiting sexism and Orientalism to the whole affair, notwithstanding the generally liberal, often forthrightly anti-racist ethos of Fuller’s work. (He would later invert House of Bamboo after a fashion in his groundbreaking, LA-set 1959 noir, The Crimson Kimono, in which James Shigeta plays the Japanese-American detective hero.)

Then there’s our thoroughly unlikable protagonist, Eddie Spannier (Robert Stack), a rumpled ex-con with a checkered Army record and, as it happens, some history with the now-deceased Webber. Reckless and entitled, Eddie disembarks in Tokyo with a lazy hunger in his eye, standing a head taller than the locals as he sniffs around for easy money. Stack plays him like a goon from a pre-war gangster flick – all appetite, no cunning – delivering clenched, charisma-free Chicago Outfit patter that feels slightly out-of-place alongside the film’s cool, midcentury tone. After he tracks down, threatens, and then brushes off Webber’s fearful, heartbroken widow, Mariko (Yoshika Yamaguchi, credited under her Hollywood moniker, Shirley Yamaguchi), it’s hard to say why one should be rooting for a thug like Eddie.

Things start to snap into focus once the viewer is introduced to Webber’s local partners, a criminal syndicate of American veterans led by a well-dressed psychopath named Dawson (Robert Ryan, paternal yet terrifying). As Eddie learns after crudely shaking down a couple of pachinko-parlor managers on the gang’s payroll, Dawson and his compatriots have set themselves up like neo-colonial crime lords, pulling off complex, daring daylight robberies using their military experience and connections. (They make a point of recruiting only dishonorably discharged vets with a penchant for lawbreaking and nothing to lose.) Dawson takes a shine to Eddie and essentially press-gangs him into the syndicate, despite the objections of the group’s hot-headed chief enforcer, Griff (Cameron Mitchell).

Although Stack’s cold-blooded meathead “hero” doesn’t exactly compel at the outset, the supporting cast holds the film together capably. This is especially the case of Yamaguchi, who takes a thankless, problematic role – part golden-hearted gangster moll and part Western geisha-girl fantasy – and delivers an emotive, tour de force performance. Eventually, however, the film’s big reveal realigns the story and works a bit of magic on Stack’s performance. Eddie is, in fact, an undercover U.S. Army detective, a fact that comes out when he meets up with his American and Japanese handlers at a Buddhist shrine, although the fallout from this revelation doesn’t truly start until he pulls Mariko into his confidence. In a single, brief scene, Stack shifts and softens his performance, revealing the vulnerable Good Cop beneath the brutish façade.

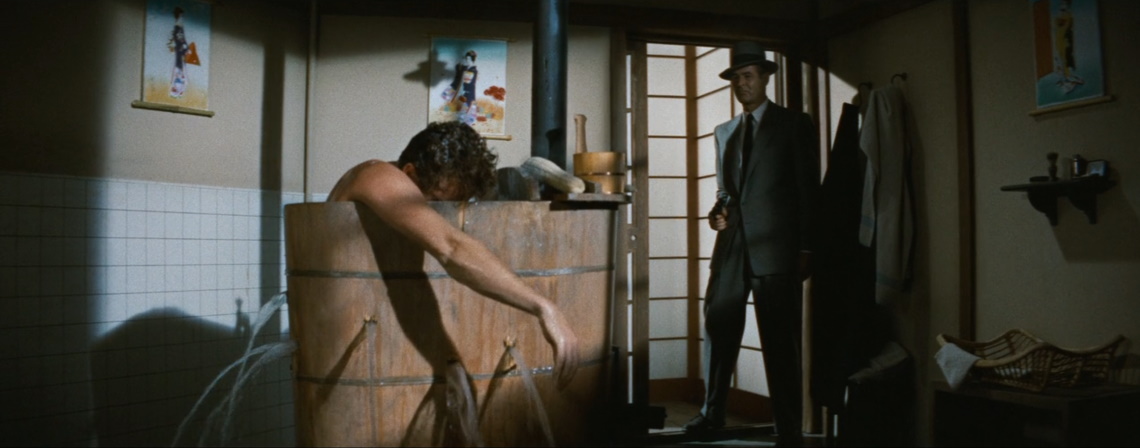

At this point, House of Bamboo is fully in familiar but richly realized territory, as the noose begins to tighten around both Eddie and Mariko and the plot attains a tense, gratifying momentum. (Squint a little and you can see the outline of another 20th-century crime-thriller masterwork, 1995’s Heat, in some of the feature’s plot points and set pieces.) However, what truly impresses about Fuller’s film, nearly seven decades later, is the grand, utterly self-assured artistry that the director and his collaborators bring to every frame of what is for all purposes a B-picture. Enthusiastically embracing the potential of CinemaScope’s vast 2.55:1 canvas, Fuller and MacDonald employ deep focus, creative angles, pronounced perspective, and sublime camera movements to elevate even the most superficially banal imagery. Every shot of the assembled two-bit goons in Dawson’s teahouse headquarters looks like a Renaissance-painting tableau, an extraordinary feat given how relaxed and unfussy it all feels. It’s not all static imagery, either: When a thug tosses Eddie bodily through a paper shoji screen, the destroyed wall allows for a reveal that made this critic literally pump his fist in delight.

The sprawling widescreen format also gives House of Bamboo’s actors an opportunity to subtly enrich the film through fine-grained performance touches in the medium-to-wide shots. While Dawson casually drops a chilling revelation on Eddie during a post-heist party, one’s eye is drawn to Yamaguchi on the far left, as Mariko attempts in vain to maintain a neutral expression and keep her chopsticks from trembling. When Dawson scolds Griff during a planning session, revealing that he will be benched for the next job, Griff starts shouting in his boss’ face, spraying spittle as his right hand twitches menacingly over a pool cue. Indeed, one could easily do a shot-by-shot breakdown of the film focused exclusively on Fuller’s brilliant blocking of his actors. Or on the razor-sharp, color-coded gangster costuming, which somehow never feels Dick Tracy cartoonish: Ryan always in gray flannel, Mitchell in slate-blue pinstripes, and a pre-Star Trek DeForest Kelley in cocoa brown. Even at its most narratively stodgy and politically retrograde, House of Bamboo is consistently that kind of movie-movie: Aesthetically striking in so many ways, it would be challenging to pick just one thing to gush about.

House of Bamboo is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel. However, the film is leaving the service after Sept. 30. Given that it is currently out-of-print on DVD and Blu-ray, we recommend that you catch it on Criterion as soon as possible.

Rating: B+

Further Viewing: Fallen Angel (1945), The Street with No Name (1948), The Steel Helmet (1951), Niagara (1953), Japanese War Bride (1954), Pickup on South Street (1953), Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), Bigger Than Life (1956), Written on the Wind (1956), The Red Kimono (1959).