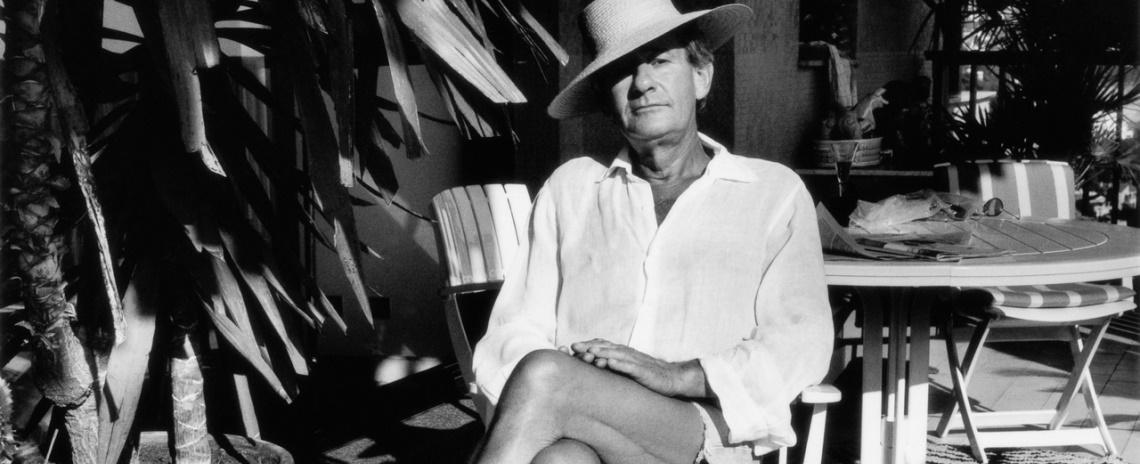

The tragic death of legendary fashion photographer Helmut Newton 16 years ago brought a difficult life and a complex body of work to an abrupt end. While departing the famed Los Angeles hotel Chateau Marmont at the age of 83, Newton was involved in a car accident on Sunset Boulevard, later dying from his injuries. The irony of one of fashion’s most transgressive, openly kinky artists perishing in such a way was not lost on fans or critics. His wife of over 55 years, photographer June Brown (professionally known by her pseudonym, Alice Springs), captured photos of Newton’s final hours from his bedside at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The images could have passed for Newton’s own work if he — hooked up to countless machines in an attempt to save his life — had been a young, blonde bombshell rather than an octogenarian. Documentarian Gero von Boehm doesn’t focus on the famous photographer’s final moments, however. His latest film, Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful, prioritizes the King of Kink’s prolific epoch that stretched from the 1970s to well into the 90s.

Helmut Newton was truly strange. It’s one of the first things everyone noticed about him, and as a result, it’s one of the defining characteristics of his exceptional portfolio. However, as The Bad and the Beautiful posits, the strangeness that permeates his primarily black-and-white photography is anything but derivative. Director von Boehm uses archival footage of Newton and new interviews with collaborators to convey how Newton’s provocative (and borderline sadomasochistic) shoots rocked the fashion world to its core. The film covers his formative years as a teen in 1940s Germany, his nascent career as an esoteric photographer in 1960s Paris, and his decades-long tenure as a sought-after contributor for magazines like Vogue and Playboy.

Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, singer Grace Jones, actresses Isabella Rossellini and Charlotte Rampling, and a whole slew of Newton’s favorite models all provide extensive and glowing talking-head segments. Each interviewee gushes over the man’s aggressively unique style, while glossing over the backlash provoked by some of his more outrageous shoots. One model, frequent Newton collaborator Nadja Auermann, seems to have been included in the documentary solely to dismiss any controversy linked to a particularly notorious shoot. Von Boehm will show off an egregious set of images, then bring Auermann out to defuse the shock with some variation on: “Critics said we were promoting [racism, sexism, ableism, etc.] with those photos, but we weren’t at all!” While it is often revealing to hear first-hand accounts of what it was like to work with Newton, the overwhelmingly positive tone of every single interview makes the documentary feel excessively hagiographic.

This is how von Boehm structures the film’s entire first hour. By using archival footage of Newton — seemingly captured with a personal camcorder — and splicing it to stylized montages and interviews with the photographer’s favorite colleagues, the director efficiently runs through the man’s most iconic shoots. From David Lynch and Isabella Rossellini’s absurdist couple photos to the much-ballyhooed “disability shoot” to the seminal Bulgari chicken ad, Newton’s more famous works each get a minute in the spotlight, while the rest of his oeuvre barely receives more than a passing glance. This means, on the whole, The Bad and the Beautiful is better suited to viewers who are unfamiliar with the photographer, as opposed to fans looking for a deep dive into his career and process.

After covering Newton’s most popular period of work, von Boehm spends some time on an era of the man’s life that is just as interesting as his professional zenith: His teenage years in Germany during Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. With Nazi propagandists like Leni Riefenstahl as only available inspiration for a 13-year-old budding photographer like Newton, his artistic touchstones were more than a little problematic, to say the least (especially for a young Jewish boy). Thankfully, world-renowned German photographer Yva (the pseudonym for Else Ernestine Neuländer-Simon) took Newton under her wing and arduously worked to undo the damage wreaked on his adolescent mind by Nazi propaganda. Recounted firsthand with more archival footage — Newton walking through Germany and reminiscing about his upbringing — the documentary’s final third is just as fascinating as what preceded it. This is mostly due to the way that von Boehm lets Newton speak for himself, rather than relying on those who worked with him to flesh out his past.

Ultimately, the question of whether or not Helmut Newton was a misogynist or a deviant is answered the same way, again and again, by the subjects he photographed. From Jones to Rossellini to the many models he shot throughout the decades, each insists that they never would have agreed to work with him if this were the case. In their words, by choosing to do these shockingly vulgar, overly-fetishized, and stylishly profane shoots, Newton allowed his feminine subjects to be empowered, not degraded. For this reason, The Bad and the Beautiful argues that the controversies never really had a negative impact on Newton’s legacy. Newton was comfortable being shamelessly weird and offensive long before anyone else in the industry dared to walk the walk. Gero von Boehm’s documentary might often feel like a glorified slideshow at times — How else to show off a photographer’s work on film? — but the director successfully makes his point: Helmut Newton and his immense portfolio are regularly imitated but will never be surpassed.

Rating: C+

Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful is now available to rent from Kino Marquee.