Any filmmaker who endeavors to reimagine Hellraiser, writer-director Clive Barker’s iconic 1987 feature, confronts pitfalls beyond the usual sort that frustrate horror remakes. Salvaging a once-beloved franchise from the morass of shoddy direct-to-VOD sequels is an intimidating prospect all on its own. The original Hellraiser film, however, is not merely the origin point for a gruesome, enthusiastically R-rated franchise. It is a seminal film in the history of independent British horror cinema and a rare example of a work ushered from page to screen by the original author. In directing the adaptation of his own 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart, Barker was constrained by budgetary concerns, puritanical censors, and his own admitted inexperience. However, the writer-turned-filmmaker wasn’t entirely a novice behind the camera – his early queer shorts “The Forbidden” and “Salome” have unfortunately been fiendishly difficult to find – and Hellraiser is the kind of galvanic indie horror film that entered the world feeling like a fully realized vision, a new nightmare made flesh.

To remake Hellraiser is to intrinsically invite comparison to Barker’s groundbreaking original feature, and to wrestle with both its critical reputation as a pivotal work of queer-themed, transgressive horror and with the dwindling gorehound devotion to the dubious, 10-film franchise it spawned. However, the new film – also titled simply Hellraiser – is not really a remake, a fact that broadly works to its advantage. It is much closer to a soft reboot, serving as an indirect sequel to Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II (also written by Barker, but directed by relative newcomer Tony Randel). Rather than attempt to re-adapt The Hellbound Heart, writers Ben Collins, Luke Piotroski, and David S. Goyer treat the first two films as a template and source of inspiration, wisely ignore the other eight features, and do a little light retconning to bring some coherence to the Hellraiser mythos (such as it is).

The result is the kind of horror “legacy-quel” (ugh) that is in vogue right now, one that manages the tricky feat of being accessible to newcomers and (mostly) satisfying to longtime devotees of Barker’s work. For viewers who only know of Hellraiser as “that horror movie with Pinhead and the puzzle box,” director David Bruckner’s film serves as a fittingly gory and atmospheric introduction to Barker’s inimitable conception of Hell, one that is utterly divorced from traditional Christian theology and iconography. Meanwhile, those viewers who are old friends with the Cenobites – the series’ otherworldly order of pale-faced, sadomasochistic demon-priests – will likely find Hellraiser 2022 both reassuringly recognizable and a little uncanny.

Although the new film revisits some of the franchise’s most well-worn narrative beats, it also attempts to enclose the events of Hellraiser and Hellraiser II within a more sharply defined and elaborate Faustian world-building framework. This raises a couple of lingering questions for the longtime fan, but squint a little, and it’s easy enough to reconcile the first two films with this new Hellraiser, which also seems to draw loosely from aspects of Epic Comics’ mainline Hellraiser anthology series (1989-92). (The Saw franchise and the seminal 1987-90 syndicated horror show, Friday the 13th: The Series, also feel like key influences.) No matter how grisly its CGI-aided marvels, any horror film released directly to a Disney-owned streaming service like Hulu in 2022 is necessarily going to lose some of the radical indie grime that made Barker’s original feature so distinctive. Still, the new film feels like the least-bad possibility for Hellraiser aficionados: a robust extension and expansion that also functions as a partial rebuild of one of the genre’s most wicked and ill-treated franchises.

The new film opens with a brief prologue set in Belgrade, as an attorney named Menaker (Hiram Abbass) meets with a broker (Predrag Bjelac) to exchange a briefcase full of money for an unseen object. The action then hops across the Atlantic to a palatial Art Deco mansion in Massachusetts, where Menaker’s employer, the billionaire Voight (Goran Visnjic), is throwing an Eyes Wide Shut-style libertine gala. One of the event’s sex workers (Kit Clarke) wanders into the host’s private museum of occult objects and, at Voight’s transparently sinister encouragement, begins fiddling with a strange, baroque puzzle box. The man soon slices himself on one of the object’s numerous hidden blades, quickly falls into a hypnotic daze, and is then horrifically attacked by hooked chains that seem to emerge from nowhere – all while Voight looks on in hungry anticipation.

Six years later, the viewer is introduced to Riley (Odessa A’zion), an underemployed, recovering-ish drug addict with the kind of trust issues that makes her instinctively recoil when her rehab boyfriend, Trevor (Drew Starkey), lets slip the “L” word. Riley is currently crashing with her older brother, Matt (Brandon Flynn); his boyfriend, Colin (Adam Faison); and their roommate, Nora (Aoife Hinds) – although Riley is just about done with Matt’s lectures regarding her burnout lifestyle. Accordingly, she is intrigued when Trevor proposes a bit of criminal mischief with a big potential payday. During his day job as an art transport and storage worker, Trevor stumbled onto a nearly empty warehouse with a single cargo container, apparently forgotten by its owner. It seems too good to be true, and when the pair crack open the safe inside said container late one night, they find nothing but a mysterious puzzle box (looking quite different than when it was last seen at Voight’s manor).

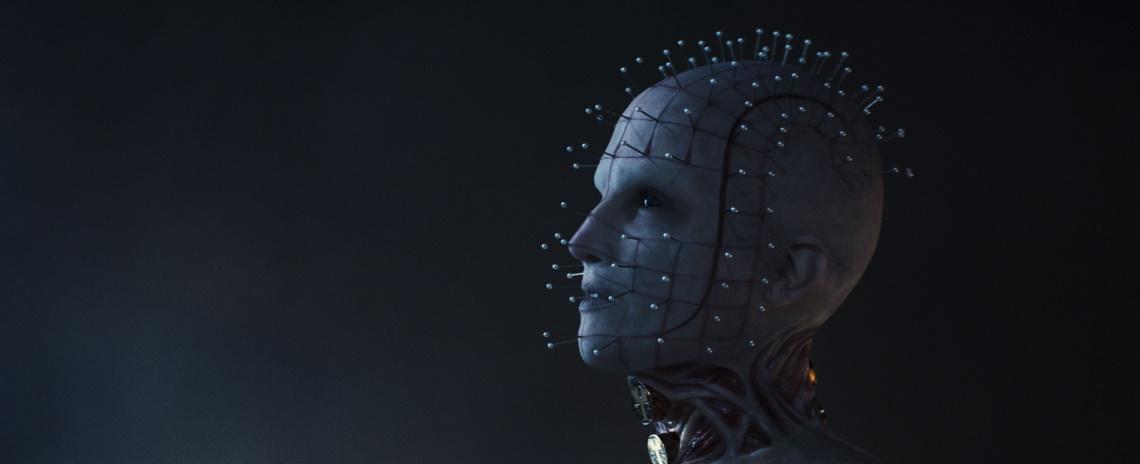

Later, emotionally distraught and freshly off the wagon, Riley is drawn to manipulate the device, transforming it into a completely new shape – while just barely avoiding a nasty cut from one of its retractable blades. This summons a group of horrifically mutilated humanoid entities, chief among them the Priest (Jamie Clayton), an androgynous fiend whose entire head is pierced by a grid of jeweled pins. As this being explains in a placid yet frightening voice that seems to reverberate inside Riley’s skull, she has unwittingly advanced the box to its next “configuration” and – cut or no cut – must either submit to the everlasting agonies of the Cenobites or offer another mortal body in her place. Unfortunately, it’s around this time that Matt decides to go looking for Riley, with predictably tragic results. This kicks off the Scooby-Doo phase of the plot, as Riley, Trevor, Colin, and Nora attempt to track down the original owner of the puzzle box, driven by the almost certainly futile hope that they might rescue Matt from the Cenobites’ grasp.

To this longtime Hellraiser enthusiast, it’s a little disappointing how much the story of this film resembles that of many other 21st-century occult-horror features. Wracked by guilt – and perhaps fueled by a little self-destructiveness – Riley throws herself into a frantic effort to uncover the nature of the puzzle box, while the secondary characters are picked off one by one in maximally gory fashion. Bruckner and his collaborators are not interested in replicating the gothic-adjacent tone of the first feature, which famously treated the Cenobites as secondary to its ghastly tale of lust, betrayal, and murder in an old, dark house. In this outing, Barker’s angels-slash-demons are unambiguously the star attraction, an always-imminent threat capable of snatching victims off to their cold, labyrinthine Hell from almost any place at any time. Weirdly, however, the film also explicitly portrays the Cenobites as a tangible, mortal peril, one that a cunning target can potentially outrun, evade, or even trick. (Maybe? David Marks’ choppy editing doesn’t help on this score, as it tends to leave key action moments feeling like a confused blur.) The needs of the scene seem to dictate Bruckner’s approach, but the inconsistency is bothersome: Are the Cenobites nigh-omnipotent devils or glorified velociraptors?

Although Hellraiser is not, strictly speaking, a slasher series, original protagonist Kirsty Cotton (Ashley Laurence) has always felt like an archetypal Final Girl, in spirit if not in fact. Fresh-faced and a touch naïve, but ultimately heroically resolute, she becomes trapped in an unthinkable situation through no fault of her own. In comparison, Riley feels like a classic Barker-esque character: a messy, broken soul whose appetites and desperation lead her to brush up against something unfathomable. To her credit, A’zion is dialed precisely into this headspace, and though Riley isn’t always a pleasant protagonist, her self-loathing volatility is key to understanding why she makes seemingly reckless choices, even as the dreadful stakes of her situation become clear.

For many Hellraiser fans, the real question is whether Clayton lives up to the towering legacy of Doug Bradley, who portrayed the Priest, aka Pinhead, in the original film and almost all of its sequels. At least half of Bradley’s screen presence was about his terrifying baritone delivery – a sharply enunciated bellow that was somehow cruel and aloof at the same time. In comparison, Clayton’s vocal performance is hushed and unnervingly cold, like some alien dominatrix. There’s something almost disturbingly maternal about her Priest, who purrs in faux-soothing tones of the eternal anguish that awaits their victims. It’s a good fit for the new film’s reimagining of the Cenobites, who no longer resemble pale-skinned humans decked out in black leather and open wounds for a particularly outré fetish night. Their appearance here is truly inhuman, naked but sexless, their waxen flesh peeled back to reveal muscles, organs, and bones. Whatever they might lack in charisma, these Cenobites unquestionably come closer to capturing the sheer otherworldly wrongness of the entities described in Barker’s novella. (One could argue that a charming Cenobite is, by definition, a failed Cenobite.)

With a few anthology segments and a couple of impressive original features to his name (The Ritual, The Night House), director Bruckner has established himself as one of the genre’s more exciting contemporary voices. Yet one can’t help but wonder if a horror filmmaker with a freakier sensibility – one more attuned to Barker’s eroticism, mysticism, and bloody-mindedness – might have coaxed a more daring and fascinating creation from the ashen remains of Hellraiser. To be sure, the filmmakers obviously have a lot of affection for the series, particularly the first two features. Composer Ben Lovett unabashedly uses melodies and motifs from Christopher Young’s superb original scores for Hellraiser and Hellbound. Moreover, the world-building that Brucker and the writers do in this film is a direct elaboration on the dark, eldritch mythology suggested by the phantasmagorical second half of Hellraiser II, a plain attempt to codify a set of horror-comic-style rules for the franchise going forward.

Although there is a certain exquisite-corpse appeal to a horror series that unfolds haphazardly from one chintzy, unnecessary sequel to the next, internal consistency is the preference in our present age of cinematic universes. Considering where the Hellraiser film series ended up blundering – from outer space to virtual reality to grindingly dismal, Witchcraft-style police procedurals – perhaps this is for the best. Barker himself attempted to reclaim the Cenobites in his 2015 novel, The Scarlet Gospels, but the result was a confounding mix of occult conspiracy and Christian theology that backpedaled on the original novella’s strangest, most disturbing elements. Given such ill-conceived developments, the track taken by Bruckner & Co. seems like the sensible one: Treat the two excellent, Barker-written films as semi-canonical and go from there. One just hopes that the next entry in the franchise – or perhaps that long-gestating HBO series – ends up in the hands of a filmmaker who is brave enough to go truly weird with it.

Rating: B-

Hellraiser will be available to stream from Hulu on Oct. 7.