Godzilla began his cinematic life as a not-so-subtle metaphor for nuclear weapons, but the pop-cultural endurance of this colossal, city-leveling radioactive reptile – arguably the great post-World War II movie monster – is attributable in part to his flexibility. While the Godzilla novice might be tempted to regard the Japanese kaiju film (and its international cousins) as a monolithic and homogeneous subgenre, the reality is much more complex and, well, pretty damn weird. The 32 official Godzilla films produced by Japanese studio Toho run the gamut, from the overt atomic terror of Ishirō Honda’s groundbreaking original (1954) to psychedelic eco-parable (Godzilla vs. Hedorah, 1971) to kiddie-flick silliness (Godzilla vs. Megalon, 1973) to exhausting sci-fi lunacy (Godzilla: Final Wars, 2004).

That said, the Godzilla franchise is currently in the depths of a profoundly pessimistic era, thematically speaking. (The “Reiwa period,” per the Japanese imperial parlance used to categorize the Toho features). The series is as blatantly apocalyptic as it’s been since Honda’s original, or at least since the grim anti-nuclear jeremiad The Return of Godzilla (1985). This shift was purportedly inspired in part by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and resulting Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. The tonal change is evident straightaway in 2016’s Shin Godzilla, a “hard reboot” that writer/co-director Hideaki Anno drenches in the paralyzing horror of a massive natural or human-made disaster. (Bizarrely yet compellingly, Anno and co-director Shinji Higuchi also turn the film into a bureaucratic satire-procedural about collective problem-solving.) Toho doubled down on this bleak tone in the Godzilla trilogy it subsequently produced with animation studio Polygon Pictures, films subtitled Planet of the Monsters (2017), City on the Edge of Battle (2018), and The Planet Eater (2018). That trio of features blends Godzilla tropes with the conventions of futurist anime to create a post-apocalyptic sci-fi saga, one in which the titular leviathan and his kaiju nemeses are reimagined in a darker, more desolate context.

The handful of American Godzilla films have always been confined to a sort of parallel, semi-embarrassing sideshow, their relationship to the Toho films primarily one of licensing. (The ‘Zilla of TriStar’s notorious 1998 Hollywood film even became a target of outright mockery in the Toho features of the early 2000s.) It’s accordingly surprising that director Gareth Edwards’ remake/reboot Godzilla (2014) has ended up feeling so consistent with the Reiwa-period Japanese features that immediately followed it. Although there is no narrative connection between those films and Edwards’, the 2014 feature captures the same feeling of Lovecraftian cosmic horror, an uncommon tone for the franchise that nonetheless seems like a natural fit. Edwards’ Godzilla has its glaring flaws – a dishwater-dull “hero,” overly dark visuals, and the elimination of its best performers before the second act – but it also has awe-inspiring and frankly terrifying monster action, superbly conveying the sense that humanity is simply beneath the notice of the planet's battling behemoths. Much like Shin Godzilla, the 2014 American feature is the uncommon disaster flick in which toppling skyscrapers, normally a source of cheap Hollywood spectacle, evoke a fitting sensation of horror and powerlessness.

The most immediately aggravating thing about the 2014’s film’s direct sequel, Godzilla: King of the Monsters, is its tepid interest in revisiting that novel mood of apocalyptic terror. The screenplay from Dougherty and Zach Shields – with an additional story credit to Max Borenstein – is most preoccupied with creating a globe-hopping action epic in the spirit of cheesy 1990s sci-fi blockbusters like Stargate (1994), Independence Day (1996), and Armageddon (1998). KotM isn’t as remotely insipid as those films, but it shares some of their more conspicuous traits: a glossy, faintly laughable futurism; a disconcerting hard-on for the U.S. military; and a script that favors earnest, hokey speeches peppered with tongue-in-cheek one-liners. Even the film’s human antagonists – a cabal of radical, violent ecoterrorists led by an ex-MI6 British mastermind (Charles Dance) – feel like refugees from some lost Arnold Schwarzenegger flick that was plucked from a Blockbuster Video shelf 25 years ago.

Dougherty has written superhero films of varying quality (X2: X-Men United, Superman Returns), but his real claim to fame among genre enthusiasts is as a director of cult horror comedies (Trick ‘r Treat, Krampus). It’s difficult to determine whether the distinctly 1990s style of his inaugural Godzilla film constitutes a semi-ironic homage to an earlier, tackier Hollywood era or just standard flattery by mimicry. Regardless, it ensures that KotM has a self-consciously schlocky quality that is at odds with the primeval, god-level horror that the film strains to evoke.

Godzilla: King of the Monsters is more of an ensemble effort than its 2014 predecessor, although the heart of the narrative is plainly the Russell family: paleobiologist mom Emma (Vera Farmiga); animal behaviorist dad Mark (Kyle Chandler); and 12-year-old daughter Madison (Millie Bobby Brown). Both adult Russells have connections with the secretive cryptozoology agency Monarch, and unfortunately, the whole family was in San Francisco at the time of Godzilla’s climactic 2014 smackdown with the parasitic MUTO super-organisms. Indeed, KotM opens with a flashback: As the victorious Godzilla lurches back into the sea, the Russells desperately search through mountains of rubble for their young son, Andrew. The loss of their oldest child drives a wedge between Emma and Mark, and five years later, they’ve split up to pursue their scientific careers on different sides of the globe. He’s filming wolf behavior in the Colorado wilderness, while she’s working at a clandestine Monarch facility in China, where Madison – in the fine tradition of many a precocious kaiju-film kid – evidently has the run of the place.

This facility houses a gestating Titan, one of several gargantuan, god-like prehistoric creatures that Monarch has discovered over the past few decades. The first of these was Godzilla, awakened by the U.S. nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll in the 1940s and ’50s. The colossal ape depicted in the 1970s-set Kong: Skull Island (2017) is another. Most of the remaining Titans appear to be slumbering, although the giant, glowing egg that houses the Chinese Titan – dubbed Mothra by the Monarch technicians – has just begun to hatch. Fortunately, Emma has recently perfected a portable bioacoustics gadget, codenamed “Orca,” which allows her to capture, remix, and broadcast the peculiar sonic language that the Titans seem to share (despite their morphological diversity). Using the Orca, she manages to calm the enormous silkworm larva that emerges from the egg. However, their human-to-monster tête-à-tête is interrupted by the literally explosive arrival of the nefarious Col. Jonah (Dance) and his militaristic tree-huggers, who are rumored to traffic in black-market Titan DNA.

Mothra manages to escape during the chaos and cocoon herself under a waterfall, but Jonah eliminates the Monarch staff, steals the Orca, and abducts both Emma and Madison – the former being one of two people in the world who understands the intricacies of the device. The other would be Mark, who years ago helped Emma design a prototype, which is why the Monarch leadership shortly appears on his doorstep in Colorado. Paleozoologists Dr. Serizawa and Dr. Graham (Ken Watanabe and Sally Hawkins, both reprising their roles from the 2014 feature) and the agency’s unctuous director of technology, Dr. Coleman (Thomas Middleditch), all plead for Mark’s assistance in tracking down the pilfered Orca. However, Mark – who has nothing but contempt for the Titans and Monarch’s benign stance toward them – is primarily concerned for the safety of his daughter and ex-wife.

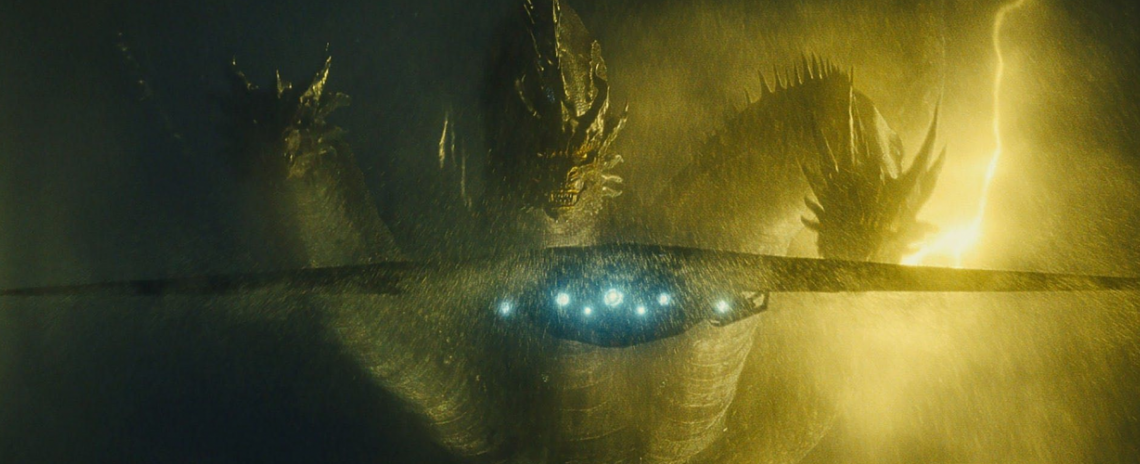

Relenting to Monarch's request, he is whisked away to an undersea research facility, one devoted to sonically tracking Godzilla’s oceanic movements in the wake of his emergence. There Mark meets more agency higher-ups, including acerbic sonographer Dr. Stanton (Bradley Whitford, essentially retreading his 2012 role from The Cabin in the Woods), Titan historian Dr. Chen (Zhang Ziyi), and Col. Foster (Aisha Hinds), a former Army Ranger officer who now leads an American special-forces unit attached to Monarch. It doesn’t take long for this group to puzzle out Jonah’s next destination: Antarctica, where a Monarch outpost stands watch over “Monster Zero,” a three-headed winged reptilian Titan encased in the polar ice. It seems that Jonah and his allies have Thanos-sized apocalyptic ambitions that have nothing to do with filching biological samples. They intend to wake the hibernating Titans one by one, re-balancing the planet’s ecosystem and healing the ravages of humankind’s millennia-long dominance. The likely demise of billions of people in this cleansing process is hand-waved away as a necessary sacrifice.

Do the dastardly eco-terrorists manage to awaken all those slumbering monsters? Does Godzilla emerge as the last best hope for humanity? Does Watanabe get to solemnly clean his glasses and speechify vaguely about the power of hope? Does one even have to ask? It’s all somewhat dismally familiar stuff, the polish lent by the 2010s visual effects notwithstanding. Admittedly, there’s a certain cheeky quality to the film’s breathless, scientifically challenged world-building that almost makes it amusing. (There’s eventually a foray into the drowned ruins of a lost, ancient civilization that is only disappointing because no one has the chutzpah to name-drop “Atlantis.”) In this, KotM has some tonal similarity to the 1950s-’70s (Shōwa period) Godzilla films, which tended to treat their science-fiction and fantasy elements with a bewildering glibness. This doesn’t exactly salvage Dougherty’s film from its own hyper-committed silliness, but it’s at least a more charitable explanation for the feature’s eye-rolling story beats than the usual studio-blockbuster stupidity.

The cast can’t do much to elevate such a trite screenplay, although they don’t really exert the effort it would take to do so. Dramatic stalwarts like Farmiga, Chandler, and Watanabe are essentially just working in their customary, sweatpants-comfortable modes. (And who can blame them? This is a $200 million Godzilla film, after all.) No one else leaves much of an impression, including Brown, who the screenwriters give zilch to work with beyond, “You’re an angsty, witless, reckless pre-teen; also, you love your mom and dad.” Every little positive morsel the film proffers is seemingly upstaged by a more pervasive negative. As an example, Hinds’ colonel is that vanishingly rare character, a black woman military commander in a Hollywood blockbuster, and almost all the named military characters are people of color. (Spoiler: They even survive to the end!) This welcome gesture of representation is soured by the film’s propagandistic, wall-to-wall obsession with weapons technology and military operations. (Most embarrassingly, the film is practically a 131-minute commercial for the V-22 Osprey aircraft, that poster child for budget-busting Defense Department boondoggles.)

None of this may matter to viewers who walk into KotM seeking the spectacle of epic monster-on-monster battles – as opposed to airtight world-building and nuanced character drama. which, if one is being honest, have never exactly been series staples. As a director, Dougherty doesn’t quite have Edwards’ affinity for bigness, a trait the latter director honed with his kaiju-on-a-shoestring 2010 debut feature, Monsters. As a filmmaker whos has previously been besotted with the beauty of autumnal and wintery nightmares, Dougherty is prone to prioritizing gorgeous, screencap-worthy shots over the overwhelming sense of scale that made Godzilla 2014 so exhilarating. This isn’t to say that delectable visuals aren’t a welcome trait in a film like KotM, which possesses two key elements that work in its favor: plenty of monsters and plenty of locations. Long before the gigantic, mutant pterosaur Rodan emerges from a Mexican volcano, annihilating a city merely by flying over it, it’s obvious that the film has poured its passion into art direction and visual effects, with creature design an obvious standout. Godzilla, Mothra, and Rodan are the marquee stars here, along with long-time Godzilla rival King Ghidorah, although KotM also offers up a cavalcade of original supporting Titans, many of whom suggest Toho kaiju like Anguirus (Godzilla Raids Again, 1955) and Kumonga (Son of Godzilla, 1967).

The film’s monsters are rendered with phenomenal attention to detail, evincing a mindful effort to visually distinguish them from one another, perhaps in recognition of the way that Godzilla’s early Shōwa-period foes often blended together into one grayish-green reptilian blur. Ghidorah’s design here is more explicitly mythological than in previous iterations, evoking a Chinese dragon rather a than a real-world animal. (There’s also a handmade “offness” to his golden scaly hide and facial features that suggests the stop-motion monsters of Ray Harryhausen.) Mothra has a luminous, almost angelic appearance in this film that sets her apart from the rest of the Titans, who tend toward more bestial or repulsive forms. The film even manages to find a roundabout way to work in the Shobijin, the twin fairies that traditionally serve as Mothra’s heralds and priestesses in the Toho films.

This is emblematic of one of the things that King of the Monsters does best: shameless, downright giddy Godzilla fan service. The film’s story lifts elements from several Toho features, most prominently the Godzilla-vs.-Ghidorah showdown Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965). However, the real appeal for kaiju devotees mostly lies in the little details, such as the plot nods to the original Godzilla – an “Oxygen Destroyer” superweapon makes an appearance – and Bear McCreary’s score, which reworks motifs from Akira Ifukube’s thunderous 1954 compositions. More generally, KotM is a film that understands the sheer, visceral thrill of a giant monster fight. The Titans clash in a variety of vivid arenas, from an Antarctic glacier howling with wind and snow to a burning, tornado-wracked Washington, D.C. Although Godzilla 2014 captured the size of its creatures better, KotM’s monster action is superior overall: a succession of vicious, animalistic death matches full of slashing, smashing, and writhing, all lit by crackling energy. Unlike the anonymous, eldritch leviathans in Pacific Rim (2013), the giants of KotM have personality, befitting a roster of movie monsters that have endured for decades.

Here and there, Dougherty exhibits an affinity for apocalyptic destruction that can be creative in is jaw-dropping splendor. There’s a moment when the smoldering Rodan obliterates an entire squadron of fighter jets simply by doing a barrel roll, a turn of events that prompts “Did that just happen?” shell shock from characters and audience alike. All this chaos is rendered with an almost painterly loveliness that can be jarring, given the popcorn-flick content on display. Simply put, King of the Monsters is an absurdly gorgeous film, at least at the Titan scale. Many of the film’s wide shots of battling monsters look like nothing so much as Rembrandt landscapes, full of deep shadow, glowing color, and menacing walls of cloud. There’s also more than a little Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel on display, with their swarming, chiaroscuro visions of Judgment and Hell. For a Godzilla aficionado, these sort of gnarly thrills and aesthetic delights are more than worth the price of some dopey dialogue and an insipid story. For everyone else ... well, there’s always the forthcoming showdown between the King of Monsters and the King of Skull Island. Or perhaps a nuanced character drama would be best instead.

Rating: C+