There are currently no Marilyn Monroe movies streaming on Netflix. There is, however, a movie about Marilyn Monroe (at least ostensibly): Blonde, filmmaker Andrew Dominik’s loose adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ titular novel (itself a loose retelling of the Old Hollywood icon’s tragically short 36-year life). It recalls Mank (2020) in this way: The streamer does not offer subscribers any films written by Herman J. Mankiewicz — not even Citizen Kane (1941), the Orson Welles production on which David Fincher’s film centers — but it gladly offers up a feature about Mankiewicz that is markedly worse than any work on which the man has a screenwriting credit. It’s the same for Monroe. Blonde is never clear on where the blame for this inaccessibility — to the star’s on-screen persona, to the woman behind the façade, to the true meaning behind her enduring legacy — should lie. Nevertheless, by its close, it has pointed fingers at just about everybody (including the audience).

Initially, Blonde targets Monroe’s — er, Norma Jeane’s — mother, Gladys (Julianne Nicholson). Depicted as an erratic, frequently abusive woman who misleads her daughter about the true identity of her father, Gladys and her terrible parenting prove to be recurring themes in Dominik’s film. A particularly intense series of events — a blazing wildfire, a botched drowning, a cry for help — leads to the separation of Gladys and Norma. The pair are institutionalized, the former to a psychiatric hospital and the latter to an orphanage, and here the target shifts from a sole oppressor to a systematic one. Then, Dominik jumps forward: Norma Jeane — stage name Marilyn Monroe — is featured on magazine covers, postcards, wall calendars, and more. These are not as traditionally classy as the ones typically graced by Hollywood royalty, but Monroe isn’t there just yet. Her star is still rising, and any opportunity in front of a camera seems like a good one. (Wait … are photographers to blame for Monroe’s eventual fate?)

The first act continues to pinball like this — reminiscent of another frenetic biography from earlier this year, Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis (2022) — until Jeane lands a major part in 1952’s Don’t Bother to Knock. Dominik leads the viewer to believe this was Monroe’s first starring role, when she has in fact been in 17 credited performances that predate it. This is neither the first nor the last creative liberty in Blonde. Recall: This is an adaptation of an adaptation of a life someone actually lived. (The hairs are there for the splitting, but it’d be a worthless and tiresome endeavor.) As Monroe’s career proliferates, Jeane’s personal life debilitates. Casting couches, scandalous trysts, physical, emotional, and substance abuse … Norma’s life was never exactly sunny, but there was always hope. Hope to be reunited with a loving mother and father. Hope to land that big break. Hope to find the right person and start a family. Hope for acclaim, for respect, for freedom. Hope for true, lasting happiness. Even before the real brutality begins, it’s clear she’s never going to get it. Not even from Blonde itself.

Dominik’s first narrative feature in a decade had been in various stages of development since before Killing Them Softly (2012), dating at least as far back as 2010. It’s a fate other Marilyn Monroe biopics have met before. David Lynch and Mark Frost had a project based on Anthony Summers’ Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe sitting on the back burner for much of the late ’80s before they extracted a few ideas and injected them into Twin Peaks (1990-91). Perhaps there’s some grand, cosmic Hollywood movie magic at play here. Maybe it’s a story that doesn’t need to be told so literally. After all, Blonde — for all its alleged subversions of genre tropes — offers very little that hasn’t already been said again and again and again since What Price Hollywood? (1932) or earlier. Did you know that some of the film industry’s very brightest stars had horrendous upbringings, overcame all odds to achieve massive success, faced unspeakable horrors at the highest rung, and soon found themselves tumbling back down the ladder to success, plummeting toward an untimely end?

This rags-to-riches perspective is no doubt one of the least interesting ways to analyze Jeane’s life. The far more captivating angle is that of parentage, present from the very first scene — as Gladys lies to young Norma about her father — and acting as a throughline to the final, transcendent, lonely scene. If only the film could have spent more time here, exploring legacy as it relates to Monroe’s two selves and the diametrically opposed lives they have envisioned for themselves. Does Marilyn want a family, or is that Norma seeping through the cracks? What does it say about Norma when she visits her mother in Marilyn mode? Are we to think of the Hollywood star system itself as her father? That would explain all that waxing poetic about the twinkling galaxies that sit just above the bright lights of Los Angeles. Parenthood, lineage, family, even name: Norma Jeane’s story as it is presented in Blonde is characterized by these repeated motifs, but not enough for any one of them to serve as the main idea. No, that distinct honor belongs to the finger-pointing.

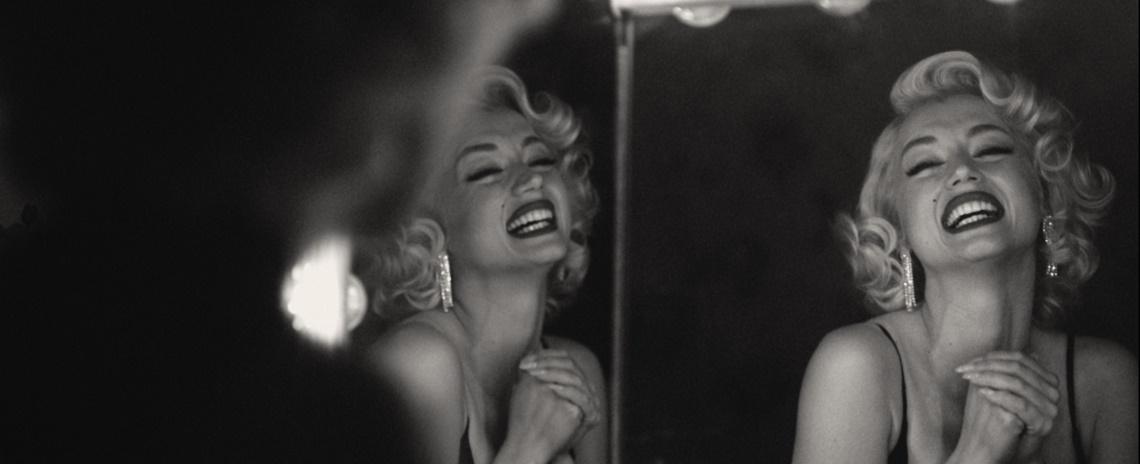

There’s blatant provocation, and then there’s Blonde. Dominik and cinematographer Chayse Irvin employ Euphoric visuals — that’s a capital E, in reference to HBO’s Euphoria (2019- ), which was, until now, the flashiest and most hyperactive direction one could find on a streaming-service original. Incessantly changing aspect ratios, camera lenses, color palettes, and points of view (seemingly at whim), Blonde goes places and does things that notoriously scored it an NC-17 rating. Subtlety and nuance were not on the call sheet, nor do they make any uncredited cameos. Dominik and company want viewers to see, feel, and experience everything that Monroe was put through. If nothing else, Blonde is certainly more than capable of eliciting an emotional reaction from even the most resolute viewer. Apart from Ana de Armas’ performance, these shots — while sometimes upsetting, sometimes absurd, sometimes both at once (as when the camera zooms out of an especially stomach-churning sequence to reveal a theater full of spectators watching it on a big screen) — prove to be quite searing, for better or worse.

After an exhausting, nearly three-hour runtime, no individual or institution under the sun (or the Hollywoodland sign) is safe from Blonde’s scorn. Norma Jeane’s mother, the neighbors who put her into foster care, the degenerate executives who took advantage of her star-studded dreams, the litany of male suitors who did the same under different pretenses … it’s one long wretched, uncomfortable, unforgiving accusation, screamed at maximum volume: Monroe and Jeane gave their lives for humanity’s entertainment. In deifying a fallen star, the filmmaker leaves it to the audience to buy or refuse what Blonde is selling, or to choose agnosticism. It’s also the closest thing to a 21st-century adaptation of Kenneth Anger’s notorious (and highly contested) Golden Age exposé Hollywood Babylon. It feels apt to cite that book’s New York Times review: “If a book such as this can be said to have charm, it lies in the fact that here is a book without one single redeeming merit.” One hesitates to throw out words such as “irredeemable” or “meritless” in regard to Blonde — due in large part to the strength on display from de Armas and Irvin, among others — but one is just as reluctant to dive into anything as shallow as this.

Rating: C

Blonde will be available to stream from Netflix on Sept. 28.